Archive for year: 2019

Foresight for Practical Strategy September 2019

/0 Comments/by adminAre Long Range EVs Really The Answer?

Henry Ford is supposed to have once said that if he had asked his customers want they wanted they would have asked for faster horses.

The The Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE) has just published an excellent report entitled:

Electric Vehicle Uptake: Modelling a Global Phenomenon

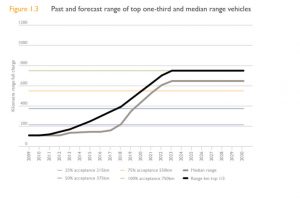

It is a great resource for thinking about adoption scenarios for electric cars but I need to quibble with one major assumption. Very early in the report, they publish this graph:

The main grey line in the graph is the forecast for the media range electric vehicle over time and they are forecasting that this will steadily grow to 650 kilometres over the next few years. This, in turn, appears to be predicated on the assumption that you cannot get adoption unless this is the case. In turn, this is based on some UBS survey work on the amount of range people want.

This is a really important assumption because it feeds into the rest of the assumptions they have made in their forecasts and I would like to posit that it is analogous to the Henry Ford quote (apocryphal or not). If we expect that ranges need to be higher this means that battery sizes need to be larger. If we expect that battery sizes need to be larger then the cost of electric cars stays higher for longer because reductions in battery costs per kWh are offset by the growth in battery sizes. This all feeds into adoption rates because the cost difference between electric cars and fossil fuel cars is one of the main barriers to adoption and battery packs are the main cause of cost differences.

I would argue that while battery size and range is a significant issue for a significant minority of people the reality is totally different for the following reasons (Using Australian examples):

- Most people drive less than 300km a week so a range of 400 km with only one weekly charge will be sufficient for their needs.

- Many families have more than one vehicle. My view is that the adoption pathway for many people will be purchasing an electric car once they are cheap enough and maintaining their newest fossil fuel vehicle for longer trips. They will use their electric vehicle as their primary transport because it will be cheaper to run. This means that on a kilometres travelled basis the change to electric vehicles will occur at a faster rate than new car purchases might indicate. It also suggests faster uptake because these people will be turning over their oldest fossil fuel vehicle and so will be in the market for a new vehicle earlier in the cycle.

- An Uber driver driving 75,000 km a year is only driving a little over 300 km a day on a 5 day a week basis for 48 weeks of the year. They can charge overnight at a low tariff in a vehicle that has a 400km range

All of these scenarios are predicated on having reasonable charging access for a vehicle either at home or at a work/travel/shopping destination.

So I would argue that the assumptions built into the BITRE report understate the potential for adoption and are based on the survey respondents not really knowing what they want until they get it.

I have published more detail on some of these issues previously. A good starting point is:

The Future of Electric Cars in Australia Part 4 – The Early Majority

Soon I will publish all my assumptions and my modeling.

I look forward to other people pulling all of that apart to improve my thinking

Paul Higgins

Libraries – What Might the Future Hold? July 2019

/0 Comments/by Paul HigginsAn Introduction to Wardley Mapping and Foresight August 2019

/0 Comments/by Paul HigginsForesight for Practical Strategy: Ballarat June 2019

/0 Comments/by Paul HigginsIs a Tesla Model 3 Really Cheaper to Own than A Toyota Camry? Part 2 – Australia

It turns out there is a huge difference between owning a Tesla 3 in The USA versus Australia. The Tesla is still way more expensive to own in Australia despite lower operating costs.